Best practices for investigating work-related vehicle incidents

Published 05/01/26 | Read time 12 min

Best practices for investigating work-related vehicle incidents

Published 05/01/26 | Read time 12 min

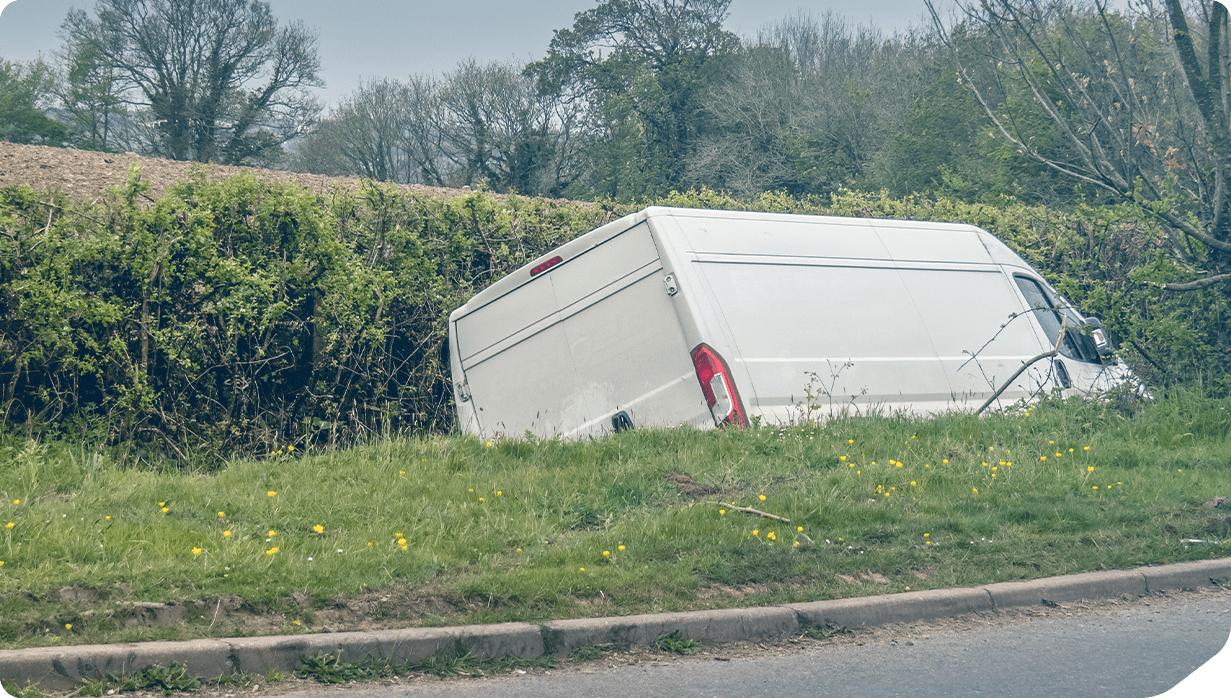

Work-related driving remains one of the most hazardous activities employers ask their staff to undertake. Despite its routine nature, driving for work contributes to a disproportionate share of serious injuries and fatalities on UK roads. When a crash occurs involving an employee behind the wheel, the immediate concern is often the driver’s actions. But good practice demands a broader lens – one that scrutinises organisational systems, culture, and oversight. Was the driver fatigued due to poor scheduling? Were they answering calls because company policy permits it? Did the business fail to enforce vehicle safety checks or provide adequate training?

This FleetInsight outlines best practice for employers conducting internal investigations into vehicle-related incidents, drawing on the National Highways Guide to Incident Investigations. It offers a structured, fair, and proactive approach to uncovering causes, identifying organisational shortcomings, and implementing meaningful change.

Why investigate incidents?

Legal duty

Under the Health and Safety at Work Act 1974, employers must do everything “reasonably practicable” to ensure the safety of employees and others affected by their operations. This includes managing occupational road risk. A failure to investigate incidents thoroughly could expose the organisation to legal scrutiny, especially in cases involving serious injury or death.

Financial risk

The cost of a single collision can be staggering. Beyond vehicle repairs and insurance excesses, employers face lost productivity, staff absence, reputational damage, and increased premiums. Effective investigations help prevent recurrence, saving money, and protecting business continuity.

Moral responsibility

Employers have a moral duty to protect their workforce and the public. Investigating incidents thoroughly demonstrates a commitment to safety, transparency, and continuous improvement. It also supports a positive safety culture – one where lessons are learned, not buried.

Principles of a good investigation

A robust internal investigation should be more than a procedural checkbox. It must serve as a strategic tool for organisational learning and risk mitigation which means the quality of an investigation directly influences future safety outcomes. It’s not just about identifying what went wrong, but about understanding how systems, culture, and leadership may have contributed to the incident. A well-conducted investigation builds trust, drives improvement, and reinforces the employer’s duty of care.

A robust internal investigation should be:

- Fact-based: Focused on evidence, not assumptions.

- Systemic: Exploring organisational factors, not just individual behaviour.

- Non-punitive: Aimed at learning, not blame.

- Timely: Conducted promptly to preserve evidence and memory.

- Structured: Following a clear methodology and reporting framework.

The goal is not simply to determine fault, but to understand what happened, why it happened, and how to prevent it from happening again.

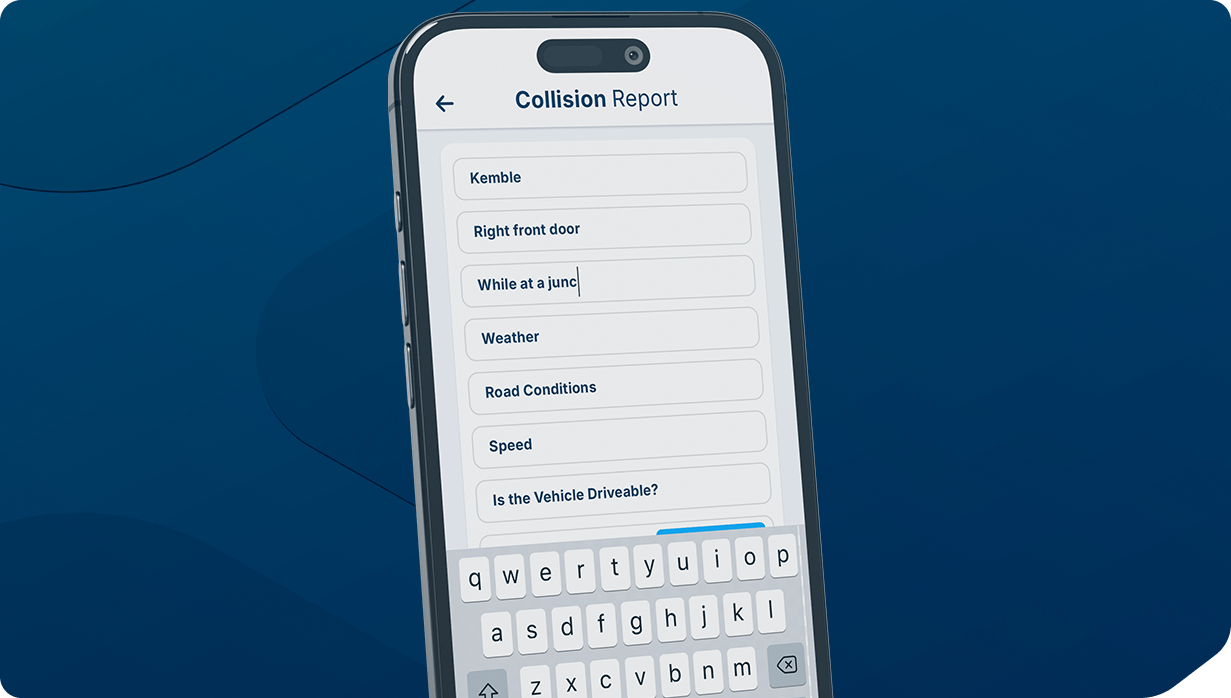

Immediate information collection

The moments immediately following a crash are critical for capturing accurate, unfiltered data. Employers should provide drivers with the tools and training to document key facts at the scene, even under stress. This early evidence can clarify timelines, identify contributing factors, and prevent reliance on memory alone. If vehicles are equipped with telematics or dashcams, integrating digital data with driver observations strengthens the investigative foundation and ensures nothing vital is overlooked.

If the driver is safe and able, they should collect key data at the scene:

- Time, date, and location of the incident.

- Journey details (start time, purpose, destination).

- Environmental conditions (weather, road surface, visibility).

- Vehicle positions and direction of travel.

- Photographs, sketches, and dashcam footage.

- Details of other parties involved and witnesses.

- Personal factors (fatigue, stress, medical episodes).

This initial data forms the foundation of the investigation and should be captured using a standardised form such as the “bump card” included in the National Highways Guide to Incident Investigations available on the Driving for Better Business website.

Understanding incident causation

To prevent future incidents, employers must move beyond surface-level explanations and embrace a layered analysis of causation. This means distinguishing between what happened (immediate cause), why it happened (underlying cause), and what systemic conditions allowed it to happen (root cause). In fleet management, this approach is essential for identifying organisational blind spots such as weak policy enforcement or cultural norms that tolerate risk. By mapping these layers, employers can design interventions that address not just symptoms, but the structural issues that enable them.

Immediate causes

These are the direct actions or events that led to the crash, e.g., the driver was speeding or distracted. While easy to identify, they often mask deeper issues.

Underlying causes

These relate to organisational systems and conditions that allowed the immediate cause to occur. Examples include:

- Lack of training or induction.

- Inadequate journey planning.

- Poor enforcement of mobile phone policies.

- Absence of fatigue management protocols.

Root causes

These are the fundamental cultural or structural issues that underpin the underlying causes. They may include:

- Weak safety leadership.

- Poor communication across departments.

- Inadequate resource allocation.

- Lack of psychological safety (e.g., fear of reporting fatigue).

A good investigation digs deep and moves beyond surface-level explanations to uncover systemic vulnerabilities.

The role of the investigator

The investigator plays a pivotal role in shaping the integrity and impact of the process. Their independence, skill, and mindset determine whether the investigation uncovers meaningful insights or reinforces existing biases. In fleet operations, where technical detail and human factors intersect, investigators must be equipped to interpret data, engage empathetically with staff, and challenge assumptions. They must also navigate sensitive dynamics – balancing transparency with confidentiality, and learning with accountability – to ensure the process is both fair and effective

The investigator must be:

- Independent: Not directly involved in the incident.

- Open-minded: Avoiding assumptions or bias.

- Skilled: Trained in interviewing, evidence analysis, and report writing.

They should gather a wide range of evidence, including:

- Driver training records and licence checks.

- Available driver medical information including DVSA notifiable conditions and eyesight checks.

- Mobile phone usage data.

- Vehicle telematics and maintenance logs.

- Journey planning documentation.

- Company driving for work policies and SOPs.

- Witness statements and CCTV footage.

Importantly, the investigator must avoid common pitfalls such as blaming individuals prematurely or assuming that “it’s never happened before” means it won’t happen again.

Interviewing: The PEACE framework

Interviewing is not just about gathering facts – it’s about creating space for reflection, honesty, and insight. Effective interviews are therefore central to understanding the incident. The PEACE framework, used by the police, offers a structured, psychologically safe approach that encourages openness while maintaining rigour. In the context of a crash investigation, interviews can reveal pressures, misunderstandings, or procedural gaps that aren’t visible in documentation. For fleet operators, adopting this model could help ensure that staff feel heard rather than judged, supporting a culture where lessons are shared and improvements are embraced rather than resisted.

The PEACE model:

- Planning and preparation: Know your objectives and evidence.

- Engage and explain: Set ground rules and build rapport.

- Account, clarification, challenge: Gather the interviewee’s version, probe inconsistencies.

- Closure: Summarise and confirm understanding.

- Evaluation: Reflect on what was learned and next steps.

Interviewers should use open questions, avoid jargon, and remain sensitive to the emotional state of the interviewee. Creating a psychologically safe environment encourages honesty and insight.

Organisational accountability: Beyond driver error

While it may be tempting to attribute a crash to driver error, this narrow view often obscures deeper organisational failings. Employers must ask whether their policies, culture, or operational decisions contributed to the conditions that made the incident possible, which means scrutinising everything from scheduling practices to driver communication channels. Was the driver fatigued because of unrealistic shift patterns? Were they distracted by calls because the company expects constant availability? True accountability means holding the organisation to the same standard it expects of its drivers.

Key areas to examine include:

Mobile phone use

- Does company policy permit hands-free calls while driving?

- Are drivers pressured to stay constantly reachable?

- Is there a culture of multitasking behind the wheel?

Even hands-free use can impair concentration. If your standard business practices encourage or even just tolerate phone use, the organisation may bear partial responsibility.

Fatigue management

- Are shift patterns and journey lengths reasonable?

- Is rest time enforced and monitored?

- Do drivers feel safe to report tiredness without fear of reprisal?

Fatigue is a major contributor to road incidents. Employers must actively manage it and not just assume drivers will self-regulate.

Vehicle safety and maintenance

- Was the vehicle roadworthy at the time of the crash?

- Are checks documented and enforced?

- Is there a culture of reporting defects?

A failure to maintain vehicles or respond to reported issues can directly contribute to collisions.

Training and briefing

- Was the driver adequately trained for the vehicle and journey type?

- Were they briefed on risks, route, and expectations?

- Is refresher training provided regularly?

Training gaps often emerge in investigations, especially for employees who don’t see themselves as “professional” drivers.

Writing the incident report

The incident report is the formal output of the investigation, but it should also serve as a catalyst for change. A well-crafted report distils complex findings into actionable insights, enabling decision-makers to respond with clarity and confidence. Where multiple departments may be involved, such as HR, compliance, operations, finance, etc. the report must be accessible, credible, and tailored to its audience. It should not only document what happened, but also articulate what needs to change, who is responsible, and how progress will be monitored.

The incident report should include:

- Chronology of events.

- Summary of evidence.

- Analysis of immediate, underlying, and root causes.

- Recommendations for corrective actions.

- Appendices with supporting documentation.

Avoid speculation or emotive language. Use plain English and visual aids (photos, diagrams) where helpful. The report should be shared with senior management and stored securely.

What happens next?

An investigation is only as valuable as the actions it inspires. Once findings are confirmed, employers must move swiftly to implement changes, whether that means updating policies, retraining staff, or redesigning workflows. This might involve revising journey planning protocols, enhancing fatigue monitoring, or investing in safer vehicles. Crucially, these changes must be communicated clearly and reinforced consistently. Staff need to understand not just what is changing, but why – and how it will make their work safer and more sustainable.

Following the investigation, the organisation should:

- Review and update relevant policies (e.g., mobile phone use, fatigue management).

- Implement corrective actions (e.g., training, scheduling changes, vehicle upgrades).

- Communicate findings and changes to all staff.

- Monitor compliance and effectiveness of interventions.

- Support affected employees, including emotional and medical care.

- Consider legal advice and media strategy if needed.

Importantly, disciplinary decisions should be separate from the investigation process. The focus of the investigation must remain on learning and prevention.

- Recording actions: Building a defensible audit trail.

An investigation doesn’t end when the report is filed – it continues through the actions taken in response. To demonstrate that lessons have been learned and risks addressed, employers must record what was done, when, by whom, and why. This audit trail is not just a formality. It is a vital part of legal compliance, operational transparency, and continuous improvement which means documenting every step taken after the incident:

- Policy updates: Was the mobile phone policy revised? Were fatigue protocols strengthened? Were these changes effectively communicated to both drivers and managers?

- Driver interventions: Was the driver assessed, coached, or retrained? Were additional licence checks or medical reviews conducted?

- Manager development: Were supervisors briefed on the findings? Was their competence reviewed or supported through training?

- System changes: Were journey planning tools updated? Was telematics data used to refine risk thresholds?

Capturing these actions in a structured, accessible format ensures that the organisation can demonstrate due diligence if challenged, whether by regulators, insurers, or internal stakeholders. It also enables performance tracking over time, helping identify patterns, measure impact, and refine future interventions.

While some organisations rely on spreadsheets or paper records, these methods can be fragmented, inconsistent, or vulnerable to loss. A dedicated fleet management platform like FleetCheck offers a more robust solution that allows employers to link incident records with follow-up actions, assign responsibilities, set review dates, and maintain a clear chain of accountability. This kind of system doesn’t just store data – it supports smarter decision-making, clearer communication, and stronger governance.

Ultimately, the organisation needs to be able to demonstrate that an incident was investigated thoroughly, that causes were understood, and that meaningful actions were taken. This is what transforms a reactive process into a proactive safety culture. It’s not about ticking boxes – it’s about building confidence, credibility, and resilience across the organisation.

Conclusion: From blame to betterment

A crash involving an employee that was driving for work at the time is not just a moment of impact – it’s a mirror reflecting the organisation’s culture, systems, and priorities. Good practice in incident investigation means looking beyond the driver’s actions to ask harder questions: did our policies enable distraction? Did our scheduling promote fatigue? Did our culture silence concerns?

By adopting a structured, fair, and systemic approach to investigations, employers can transform incidents into catalysts for change. It protects their people, fulfils their legal duties, and contributes to a safer transport sector.

And perhaps most importantly, they demonstrate that safety isn’t just a policy. It’s built into the company’s culture.